SAVE OUR SOILS

To protect the planet's soils from collapse

– and thus ourselves –

we must radically change the way we farm

Chapter II

Worn out

„We know more about the movement of celestial bodies than about the soil under our feet.“

Leonardo da Vinci

Since ancient times, the dung heap had been a stinking status symbol: The higher the animals' manure piled up in front of the farmyard, the richer the landowner. In the eighth century before our time, Greek poet Homer described how Odysseus' servants spread the manure on the fields. People had long realized that the oxen and horses that they used to pull their ploughs fertilized the fields with their excretions. Farmers who merely removed nutrients from the field with the harvest, but did not return sufficient nutrients to the soil in the form of manure, were in danger of running out of food. In fact, the increasingly depleted soils contributed significantly to the catastrophic crop failures and famines that cost millions of lives in medieval Europe. As a result, farmers developed the three-field system, the earliest form of crop rotation. From then on, summer and winter cereals were grown alternately before the land was left fallow in the third year and used as pasture. The animals' excrements fertilized the soil for the following year.

It took some more centuries before chemist Justus von Liebig formulated the principles of modern fertilization in 1840: „It must be regarded as a principle of agriculture that the soil must fully recover what has been taken from it; in what form this recovery takes place, whether in the form of excrement, ashes or bones, is probably quite indifferent.“ Liebig concluded with an almost visionary prophecy: „There will come a time when the field, when every plant that you want to grow on it, will be provided with the fertilizer it needs, which will be prepared in chemical factories.“ The „agricultural chemistry“ founded by Liebig paved the way for the industrial production of fertilizers.

The soil was now regarded as a kind of chemical depot that allowed crops to thrive as long as sufficient new nutrients and mineral salts were added to the field after the harvest. The emerging fertilizer industry soon developed into one of the driving forces of colonialism, as a global race for the deposits of the coveted mineral raw materials began. The German Empire and the British Empire fought over the tiny Pacific atoll of Nauru. Seabirds used the island as a breeding ground and over time had covered it with a meter-thick layer of excrement. The birds' droppings decomposed into rich calcium phosphate, which was in demand worldwide as guano fertilizer. Due to guano mining, the interior of Nauru still resembles a crater landscape today. On the Pacific coast of South America, in the border region between Peru, Bolivia and Chile, the hunger for the rich guano deposits even caused what became know as the „Nitrate War.“

„Bread from air“

The next breakthrough in the history of fertilizers was achieved by chemists Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch in 1911: under high temperatures and enormous pressure, they extracted the naturally occuring nitrogen from the air. "It's dripping", Fritz Haber is said to have exclaimed enthusiastically as the synthesized liquid ammonia trickled out of the apparatus. Carl Bosch made the ammonia synthesis market-ready on behalf of the Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik, better known by its acronym BASF. The first factory for large-scale industrial nitrogen fertilizer production was built at the company's headquarters in Ludwigshafen am Rhein. The Haber-Bosch process made it possible to produce "bread from air", contemporaries rejoiced. For them, synthetic fertilizers represented nothing less than a revolution in food production. Today, the nitrogen obtained in this way is the most widely used fertilizer in the world. Half of the world's population is fed on food grown with the addition of nitrogen from the Haber-Bosch process.

But first the synthesized ammonia proved its extremely destructive effect...

... in the form of explosives during World War One.

„In times of peace the scientist belongs to humanity, in war-time to his fatherland“, according to Haber, who developed the first chemical weapons. His poisonous gas was soon used during the war. Research into these chemical substances formed the basis for many pesticides, some of which are still used in agriculture today.

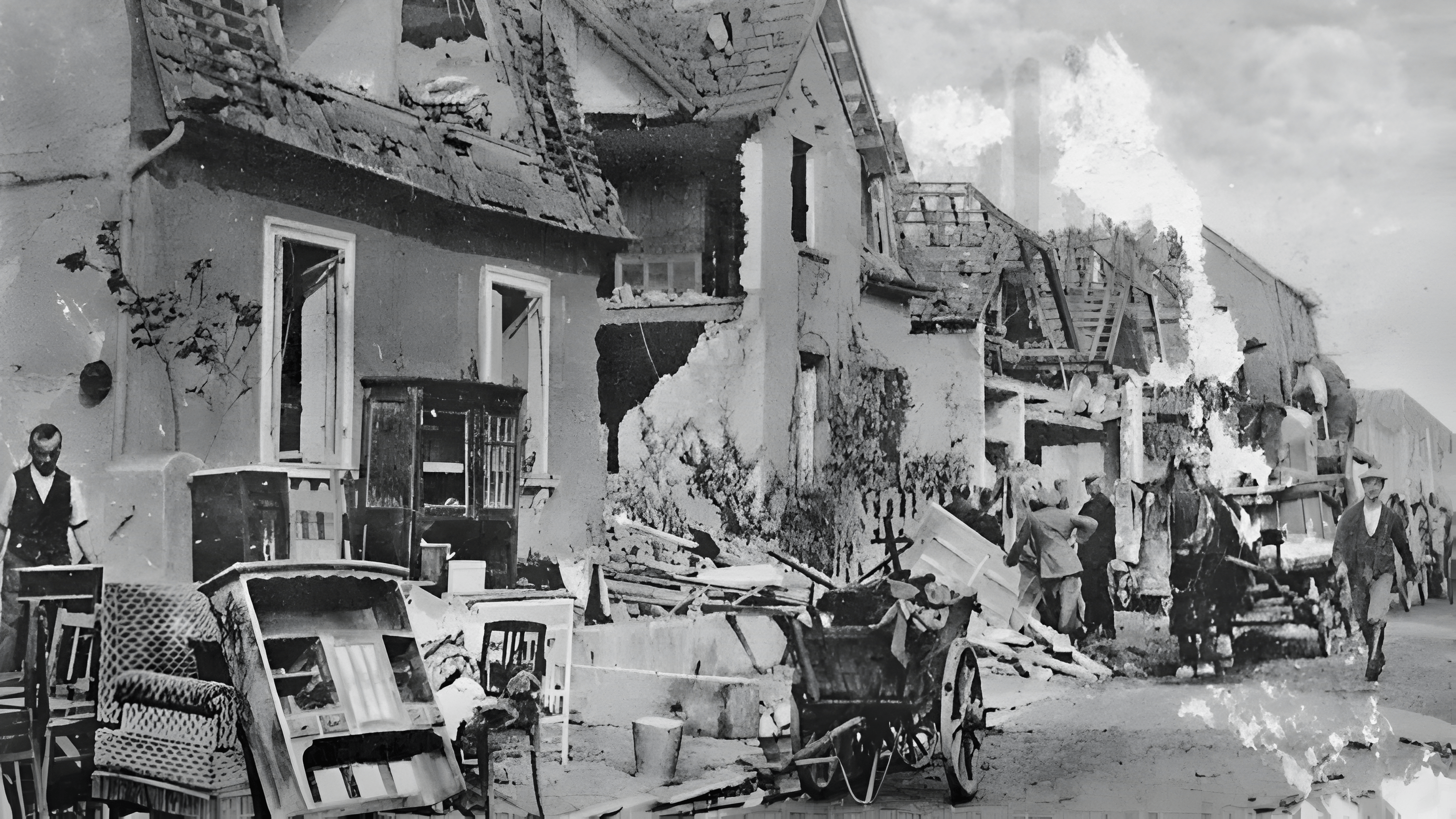

After the war, the ammonia's explosive power destroyed the BASF plant in Friedrichshafen-Oppau when a fertilizer silo exploded in 1921.

The detonation killed 559 people and damaged houses up to a distance of 75 kilometers away from the site; the bang could be heard as far away as Munich and Zurich. In terms of the number of victims, it remains the biggest accident in the history of the German chemical industry to date.

As enormous as the energy content of the chemical compounds is, so is the effort required to produce the synthetically obtained fertilizers. The Haber-Bosch process, which is usually fueled by natural gas, is responsible for one percent of global greenhouse gas emissions today. The entire agrochemical industry with its production of fertilizers and pesticides consumes more than half of the total energy used for the production of agricultural goods. In total, agriculture causes a third of all greenhouse gas emissions.

However, global agriculture could apply a third less nitrogen fertilizer to the fields – and still produce the same level of harvests. The fertilizer quantities would simply have to be better distributed around the planet, according to a recent study. The fertilizer that could contribute to higher harvests in Africa, for example, is currently being wasted elsewhere. In Europe, up to three quarters of all fields are considered to be over-fertilized – with fatal consequences for the soil.

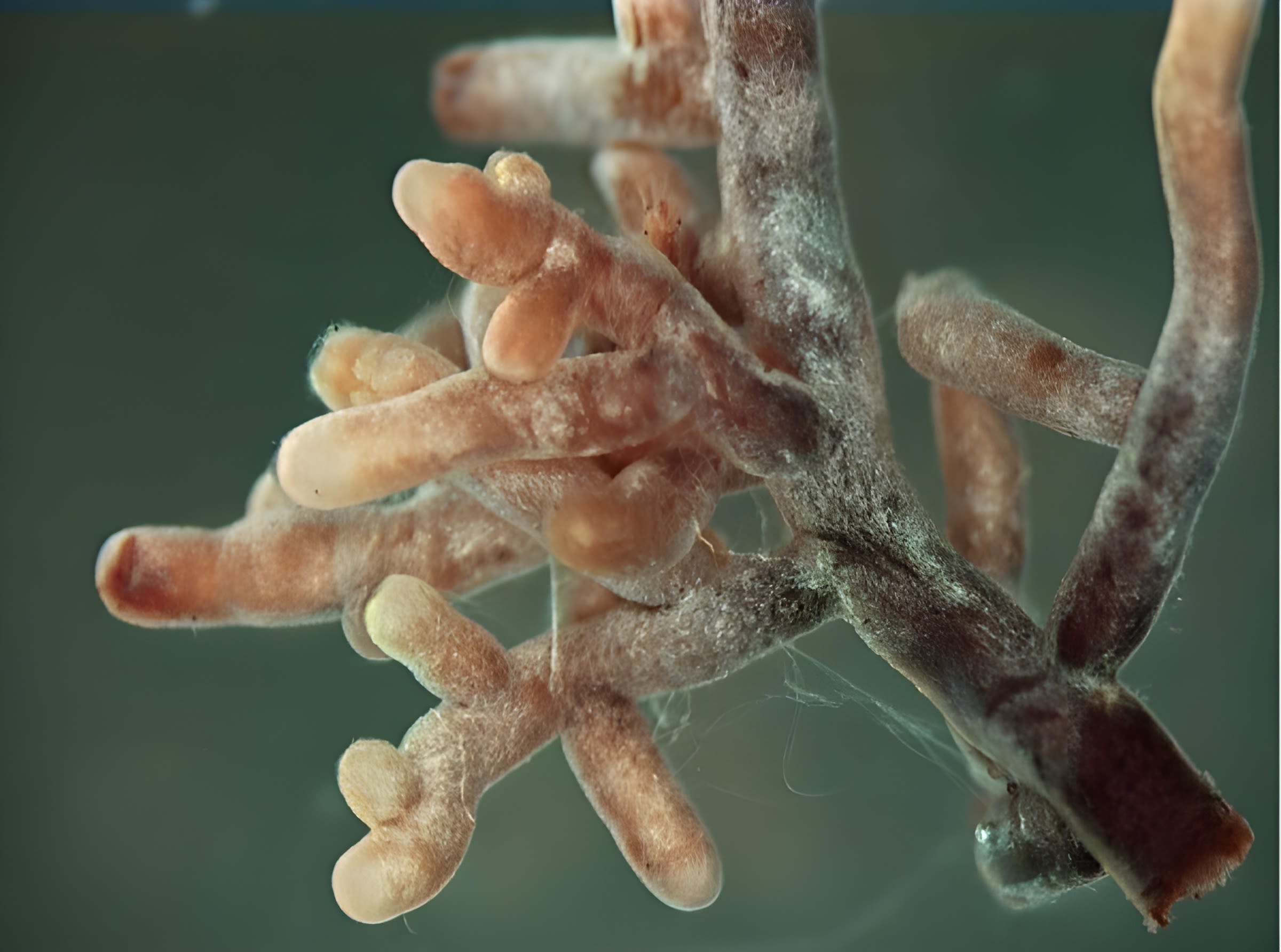

Nitrogen fertilizers, for instance, harm mycorrhizal fungi which play a prominent role in the soil. These fungi colonize the roots of plants. Research assumes that ninety percent of all plants enter into such symbioses. It was probably also myccorhiza fungi that helped the first plants leave the seas and conquer the land. The fungi provide the plants with nutrients, especially phosphate, an essential element for plant growth. In return, the fungi receive, among other things, energy-rich carbon compounds that they cannot produce themselves. A study found that the global mycorrhizal network underground can absorb up to 13 billion tons of CO2 each year – that is more than a third of all annual greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels.

Like the fingers of a glove, mycorrhizal fungi envelop these delicate root tips, protecting them and making nutrients available to the plant. Without the help of mycorrhizal fungi, most plants cannot access the phosphates bound in the soil.

Like the fingers of a glove, mycorrhizal fungi envelop these delicate root tips, protecting them and making nutrients available to the plant. Without the help of mycorrhizal fungi, most plants cannot access the phosphates bound in the soil.

If the fungi are missing, most phosphorus remains in the ground unused. Mycologist Arthur Schüssler has calculated that eighty percent of the phosphorus applied as fertilizer is never available to most crop plants because there are too few mycocorhiza fungi living in the fields. „It’s a waste that we can’t afford for much longer,“ Schüssler says.

Artificial nitrate fertilizers, on the other hand, are usually soluble in water. This is practical because their nutrients are immediately available to the plants even without fungi. But excess nitrates that are not absorbed by the plants will sooner or later be washed out of the field by the rain, causing eutrophication, an overabundance of nutrients in waterbodies. Algae thrive under these conditions, but as they rot, they deprive the water of oxygen. In the oceans this has lead to so-called „dead zones” in which there is hardly any oxygen left on the seabed. Underwater life is collapsing. One of the largest of these dead zones has been located in the Baltic Sea.

In drinking water, excessive concentrations of nitrates are considered to be carcinogenic and harmful to the health of infants in particular. The German Federal Environment Agency states: “Where agriculture is practiced, there is too much nitrate in the groundwater throughout Germany.” Almost a fifth of the groundwater across the country is permanently contaminated with the problematic nitrogen compound as a result of excessive fertilization. More and more waterworks have to dilute their groundwater with clean water in order to ensure drinking water quality.

According to the European Commission, 21 percent of the continent's soils are also contaminated with cadmium, in concentrations that significantly exceed the limit value for protecting drinking water in many places. The heavy metal, which is also considered carcinogenic, is introduced to soils primarily through phosphate-containing mineral fertilizers.

„My flock lives underground.“

Jan Wittenberg, organic farmer in Lower Saxony

While the surrounding fields are soaked with manure from the factory farms that have given this area the uncomplimentary nickname “pig belt”, Jan Wittenberg cultivates his farm near Hildesheim in the South of Lower Saxony completely without any external fertilizers. Synthetic or mineral fertilizers are taboo for his organic farm anyway. Wittenberg's secret recipe is based on diverse crop rotations, especially on the cultivation of legumes. This family of plants, also known as Fabaceae, includes beans, peas and lentils, but also clover, lupine and alfalfa. Their special feature: With the help of nodule bacteria that settle on their roots, they can bind nitrogen from the air in the soil. Nitrogen is a fundamental element of life that is essential for the metabolism and growth of plants.

Anyone who grows nutrient-hungry, particularly nitrogen-consuming crops such as potatoes or corn must ensure that the soil is supplied with enough nitrogen after harvest. As so-called nitrogen fixers, legumes have always played an important role in crop rotation. In its „Protein Plant Strategy“, the German Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Food emphasizes: „The use of legumes is of essential importance for agriculture as a whole and, in addition to the regional production of plant proteins for animal feed and human nutrition, also contributes to climate protection.“

Fruitful symbiosis: Nitrogen-binding rhizobia bacteria settle on the roots of this soy plant, which can be recognized by the “nodules” that are typical for legumes.

Fruitful symbiosis: Nitrogen-binding rhizobia bacteria settle on the roots of this soy plant, which can be recognized by the “nodules” that are typical for legumes.

The area on which lgumes are grown in the EU has more than tripled over the past ten years. For most farms, however, legumes are commercially worthless. The seeds cost money, but the ripe fruits can only be marketed in small quantities. Demand has only been slowly increasing since plant-based alternatives to meat and dairy products are en vogue. Jan Wittenberg sells his lupins, beans and lentils to a company that processes them into organic bread spreads and other protein-rich food. This way, his legumes not only impove the health of his soils, but also promote human health.

Yet, around 93 percent of all plant-based proteins in the EU still end up in the feeding trough – and that is usually filled with cheap soy from overseas. That's why most legumes rot in Europe's fields. They are plowed under as green manure. So while their cultivation does benefit the soil, the protein-rich harvest is wasted.

It is the aftermath of a little-known deal: In 1992, the EU and the US sealed the so-called Blair House Agreement. As part of the negotiations for the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which led to the founding of the World Trade Organization (WTO) a year later, the leading industrial nations reorganized the world market for grains and protein crops. The EU granted the US and later the Latin American agricultural giants Brazil and Argentina duty-free imports of protein crops, especially soy. In return, the EU developed from a net grain importer to the world's second largest grain exporter (second only to the US). One of the main reasons was that Europe's farmers increasingly fed their cattle, pigs and chickens with imported soy instead of domestic grain. The EU currently imports around two thirds of its feed protein requirements from the US and Latin America. That's why the following analysis from the 2011 study commissioned by the Greens in the European Parliament entitled „Biodiversity, not soy madness!“ still applies today: „We use areas for our calorie-destroying eating style that are no longer available to a large part of humanity.“

Jan Wittenberg has long been committed to opposing this unjust agricultural and trade policy. When thousands of people march through Berlin's government district every January under the motto „We're fed up“ to demonstrate against „agricultural factories“ and for sustainable agriculture, he drives his yellow tractor in the front row.

He also enjoys the role of agrarian rebel back home in Lower Saxony. On a cold day in March, a strong wind blows across the landscape as Wittenberg rolls into his field of freshly sprouted lupins. Without an air-conditioned cabin, he stands on his tractor, defying wind and weather.

„I'm the gateway drug“

For the living creatures underground, it is like an earthquake when a plow tears up the soil, Jan Wittenberg explains . „The fine network of fungal hyphae that runs through the entire soil is torn apart.“ With the topsoil, the whole underground ecosystem is turned upside down. Species that would otherwise never see daylight are thrown to the surface. Others, settled for life in the top few inches of topsoil, are buried.

Tilling the soil allows air to reach deeper layers, which stimulates oxygen-loving bacteria that feed on the humus. They break it down and release the nutrients bound in it for the plants. That's why the plow is so especially important for most organic farms that are not allowed to use artificial fertilizers. But the bacteria don't just extract nutrients. Their metabolism „burns” the carbon bound in the humus, carbon dioxide is „exhaled”. Plowing therefore contributes significantly to agriculture's overall emissions.

Humanity has used the plow to cultivate the soil for thousands of years. In our effort to subjugate nature, mechanical tillage meant the decisive breakthrough. Where dense vegetation covered the ground, no grain could be sown. That's why the plow is still part of the standard equipment of most farmers, especially in organic farming, which is not allowed to use herbicides. Instead of spraying synthetic “weed killers,” most organic farms simply kill unwanted plants by tilling them into the soil.

Jan Wittenberg proves that it can be done without the plow. In order to spread this knowledge, he works a side-job as a representative of a medium-sized manufacturer from Bavaria which advertises their devices as „agricultural machinery for organic farming”. Every couple of weeks, Wittenberg loads his tractor and harrow onto a large trailer and drives it across northern Germany to convince other farmers of the advantages that this agricultural machinery offers. Of the participants, he says, that one third are organic farmers, another third of farms in transition to organic, and one third of conventional farmers. Jan Wittenberg says of himself: „I am the gateway drug.”

The plow was a revolutionary invention that broke ground for agriculture as we know it today. „But looking at the advancing speed of soil degradation, the plow must be completely re-evaluated. It should not longer be seen as an achievement of civilization”, Wittenberg says. At least since the plow paved the way for European colonialism, tillage has caused devastating damage worldwide.

„The nation that destroys its soils, destroys itself.“

Franklin D. Roosevelt, 32nd president of the USA, 1933 - 1945

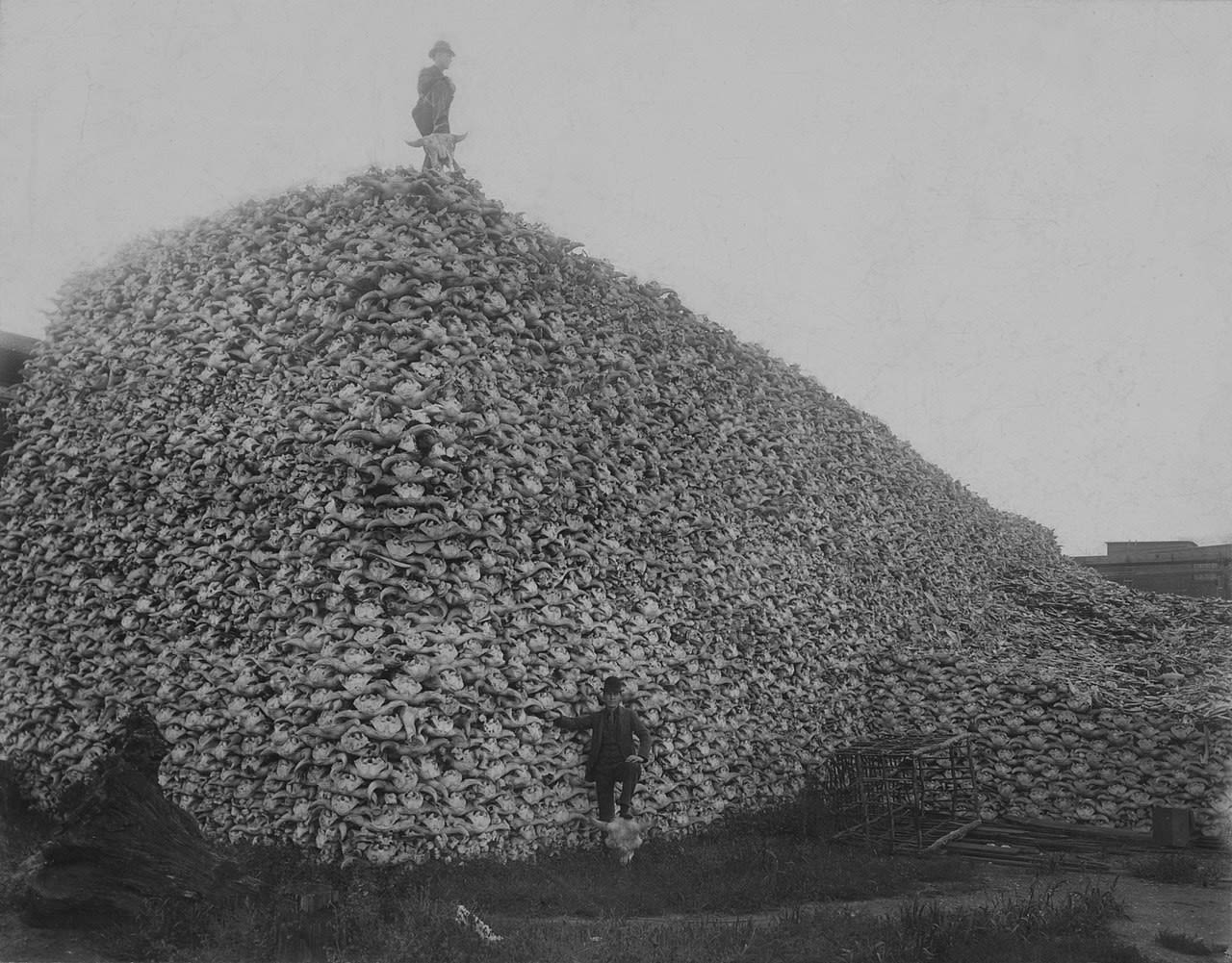

With the westward expansion, the European settlers claimed the North American prairie. First, they almost wiped out the bisons who had shaped one of the largest grassland landscapes in the world for millions of years. Their bones were ground into fertilizer.

Then they broke up the ground with their plows, which they had brought from Europe.

The wheat that they grew, however, had much shallower roots than the original prairie grasses. When the rains stopped and the plants dried up, the soil got lost.

The wind simply carried away the soil. Between 1935 and 1938, black clouds of dust repeatedly darkened the sky. On April 14, 1935, which went down in history as Black Sunday, the dust was blown all the way to the Capitol in Washington.

Erosion turned large parts of North America's prairie into what became known as the Dust Bowl. This episode is considered the worst environmental disaster in US history.

Just how devastating such dust storms can be was demonstrated on April 8, 2011 on the autobahn 19 between Berlin and Rostock, when strong wind blew the topsoil from a bare field across the highway. Within seconds the air was filled with ochre-colored dust and visibility went down to almost zero. Dozens of vehicles crashed into each other, a hazardous goods transporter caught fire. Eight people burned to death in their cars, 130 others were taken to hospital, many of them seriously injured. After the multiple collision, then then-Minister of Agriculture Till Backhaus said: „The storm stirred up the finest humus particles.“

In the federal state of Brandenburg, such sandstorms sweep through the agricultural desert year after year. Farmer Mark Dümichen has filmed many of them with his phone.

„Thanks to no-till farming, I have been able to cut the use of pesticides by two thirds, plus I only need half as much fertilizer and diesel as I used to.“

Mark Dümichen, no-till farmer in Brandenburg

The Niedere Fläming district, about an hour south of Berlin, is one of the driest regions in Germany. It is mid-June and it has not rained significantly since April. The first village ponds are already drying up once again. Here and there, you can still see the charred stumps of the pine plantations of which hundreds of hectares have burned down in recent years. Climate models predict that within a few decades, large parts of Brandenburg will have turned into steppe.

In the village of Lichterfelde, an archway leads the way into the courtyard of a four-sided farmstead. „My ancestors have been farming here since 1600,“ landlord Mark Dümichen says as he welcomes us with a firm handshake. „Somehow they seem to have managed quite well, if you look at all these buildings. Apparently, people used to be able to make a good living from farming in this area. So I can't imagine that the soils have always been in such bad condition.“ His son studies agriculture and is supposed to take over the farm one day but Dümichen gets straight to the point: „If we want to continue farming here we should come up with solutions as soon as possible. Otherwise we will be forced to quit farming in this area alltogether sooner than later.“

Before we head out into the fields we stop at the snack bar around the corner, where the local farmers meet in the morning. There is coffee on the table and half-sliced bread rolls with sausage spread from one of the pigs that Dümichen still slaughters himself. His fellow farmers serve up sad anecdotes from their everyday lives. There is the news about yet another farmer who just committed suicide in one of the nearby villages. One more farmer, they say, who could no longer endure the rising costs for fertilizers, diesel, pesticides and land lease, the seemingly endless work, just to pay off the just as endless amounts of debts. Debts that the farmers have to pay back from the ever poorer harvests they yield. Mark Dümichen makes up a calculation: „At the end of the day, I'm working for an hourly wage of 1.25 Euros.“ Why is he still doing that to himself? Dümichen talks about farmers' pride, about tradition. „Without any exaggeration: being a farmer is the most important job in the world. Who else would grow our food?“ In the morning tristesse, it becomes apparent that most farmers are trapped in a system that pays them little more than breadline wages.

In order to explain how farmers have ended up in this situation, Dümichen drives us to one of the many maize fields that dominate the entire landscape. On his neighbor's field, the corn stands waist-high but the plants look puny. Maize after maize after maize has been grown here for the past 15 years, without any crop rotation, Dümichen says with a shake of his head. The fact that such a maize monoculture promises the highest income – at least in the short term – is the root of the problem, he says. But there is more to it: „Maize germinates late. It then grows slowly at first and finally it is harvested without leaving any residues on the field. This way, the soil remains bare for most of the year.“ In the end, the whole maize plant is shredded and taken to one of the many biogas facilities. Because he needs to earn money, Dümichen also grows maize for biogas plants on some of his land. However, growing maize as an energy crop not only increases competition for land that is no longer available for food production. Several studies have shown that the profitable biogas plants can also drive up the rent prices for arable land. In the end, the fermented plant residues are brought back to the fields. Dümichen is very critical of this supposed circular economy: „This is actually nothing but a dumping site for fermentation residues,“ he says as he looks at his neighboring field. While the ferments do have a fertilizing effect, without crop rotation the soil still becomes impoverished. „This in not a living soil, it is hard as rock.“ Dust spreads in the shimmering heat as Dümichen scrapes the surface of the field with the sole of his shoe.

The ever larger farms are owned by ever fewer agricultural holding companies. These mega-farms are operated on a short-term profit basis, so their crop yields have to cover the high costs for fertilizers and pesticides. „These big farms are not interested in the long-term health of their soil“, Dümichen is convinced. If the rental prices were lower, there would be money left over that could be invested in soil maintenance, for example for the cultivation of catch crops. „But if I only have to make sure that I earn anything at all at the end of the season, then I will save money wherever I can. And it's always the soil that will suffer first under this cost pressure.“

Dümichen says that his neighbouring maize field is managed by a holding company owned by entrepreneur Siegfried Hofreiter. Starting his business from his family's small farm in Bavaria, Hofreiter had risen to become the head of KTG Agrar, the then-largest agricultural group in Europe, thanks in particular to the vast arable lands in Eastern Germany, which have been coveted by financial investors since the reunification. Until in 2016, Hofreiter landed the most expensive bankruptcy in the history of the German agricultural industry. However, just two years later, he was back in the maize and biogas plant business. The trade journal „Finance“ reported at the time that „rumors are circulating in the region that Hofreiter sees the drought catastrophe as an opportunity to return to his old business on a grand scale.“ As smaller farms have to give up their land due to poor harvests, big companies buy up the farmland. Siegfried Hofreiter was not available for an inquiry by Greenpeace Magazine; he has been in custody since November 2023 for suspected fraud in another case. One thing though is certain: Only those who maximize their yields can survive. As the small farms are dying out, the mega-farms are getting bigger and bigger. It is an unequal competition that Mark Dümichen has been trying to free himself from for the past 15 years.

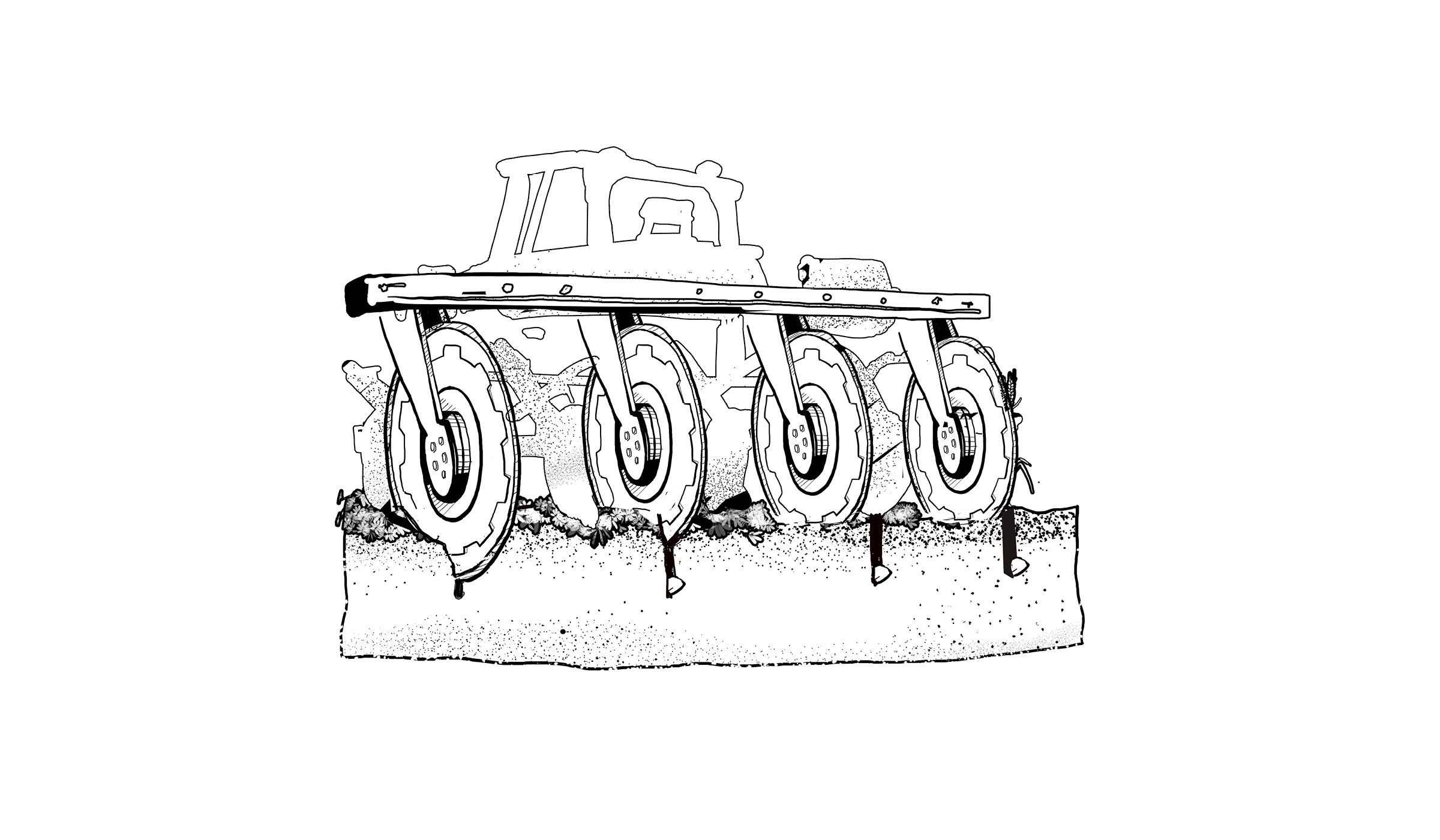

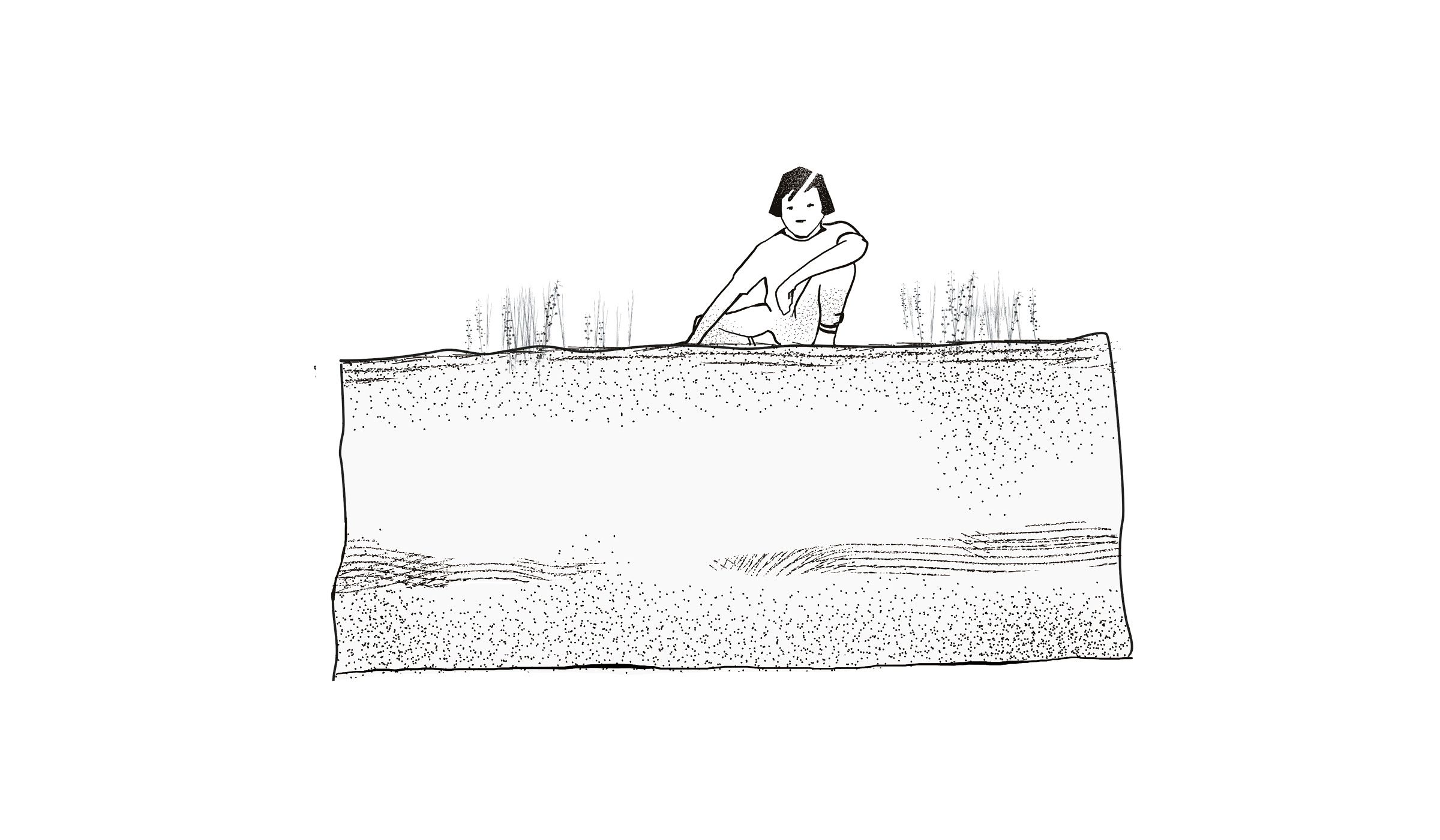

On the sandy soils of Brandenburg, in the increasingly dry climate, Mark Dümichen demonstrates how it could be done – or as he says himself, „how agriculture can have a future here at all.“ He cultivates his land using no-till farming. In this method, the seeds are sown directly into the freshly harvested stubble field or even into the previous crop that is still standing. Instead of plowing or otherwise disturbing the soil before sowing, only fine slits are cut into the soil in which the new seed can germinate, similar to using a pizza cutter.

The soil is opened only minimally to place the seeds.

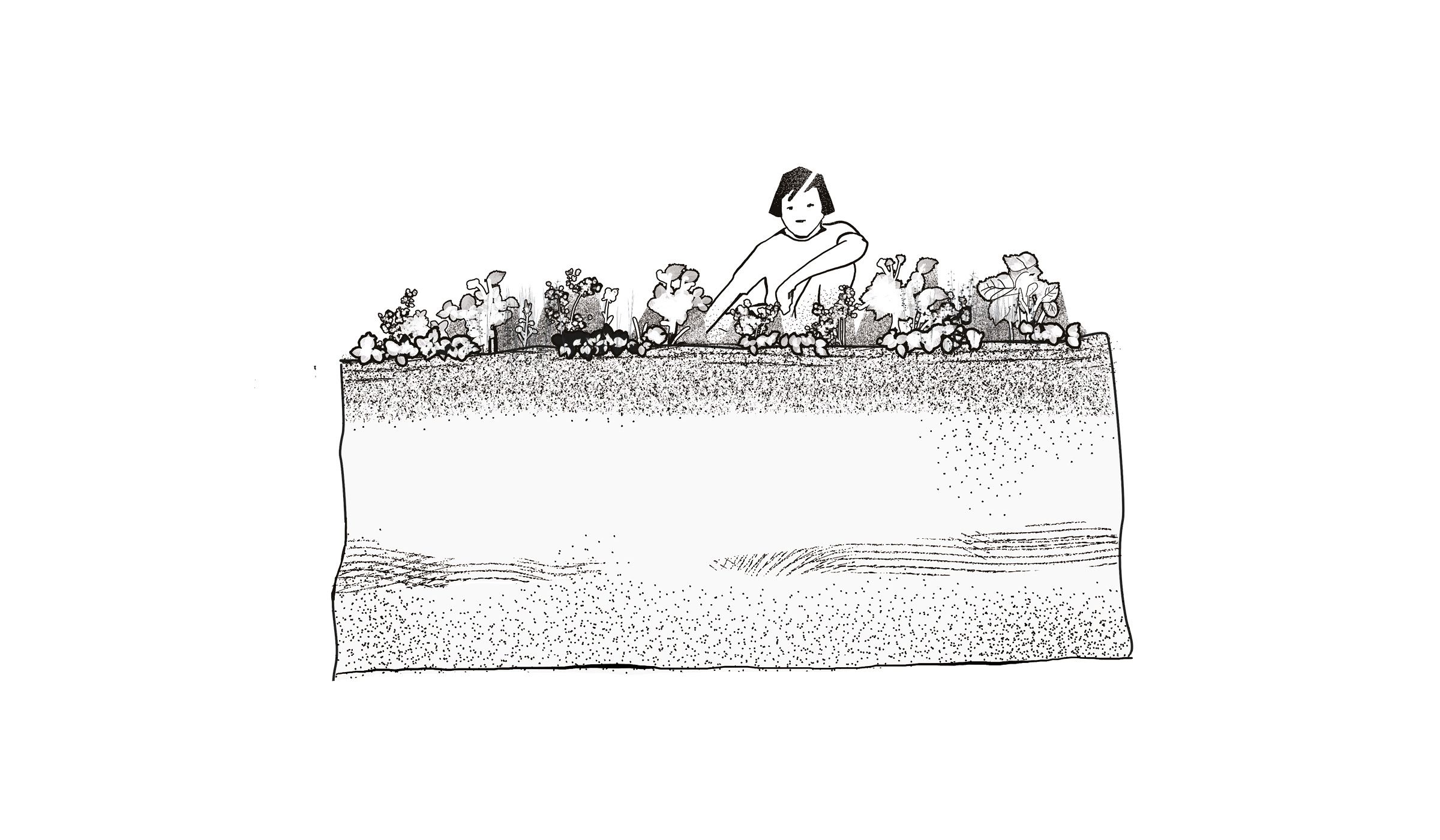

Dead catch crops and harvest residues form a mulch layer. The field therefore never lays bare, the soil is covered at all time.

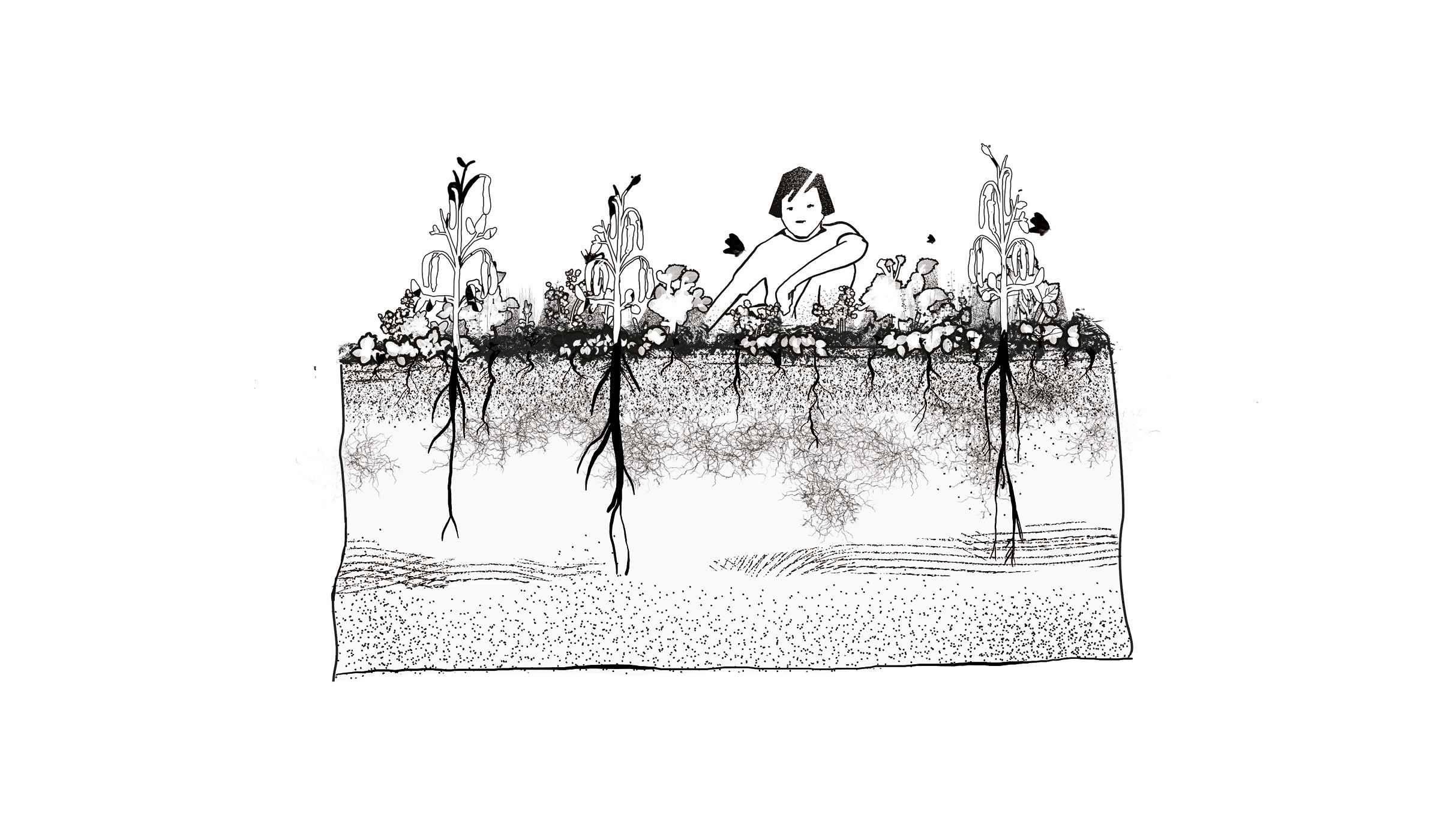

Diverse crop rotations promote soil health. They help to suppress pathogens while nutrients are returned to the soil.

The advantages are obvious: the mulch layer protects the soil from erosion and from drying out. And for the farmers, no-till is highly efficient. Dümichen does the math: Since he has switched his farm to no-till, his operating expenses have been drastically reduced. He only uses insecticides and fungicides in emergencies, he says, in most years he now manages without any pesticides at all. This is because in his undisturbed soil, beneficial organisms are better etablished and therefore able to keep pests under control. Dümichen says he is already down to half the amount of fertilizer that he used to apply. To nourish the soil life, he spreads large quantities of compost on his fields. His goal is to get away from artificial fertilizers altogether.

However, Dümichen remains reliant on one product in particular: the controversial total herbicide glyphosate, which critics link to cancer and the decline in biodiversity in the agricultural landscape.

While Dümichen emphasizes that he needs less and less glyphosate from year to year, CropLife, the lobby association of the agrochemical industry, claims: "No-till is dependent on herbicides because of the elimination of tillage for control of weeds." In no-till farming, most farmers simply spray unwanted vegetation with herbicides to kill it rather than plowing it under.

Since he has quit the fuel-guzzling work of plowing, Dümichen also needs only half as much diesel. He no longer needed soil-working machinery such as harrows and cultivators either, so he has sold them. Instead, he bought a special no-till seeding machine, imported second-hand from Brazil. There, no-till farming is booming – and so does the herbicide business.

„For every ton of grain harvested, up to ten tons of soil were lost.“

Rolf Derpsch, the pioneer of no-till farming in Latin America

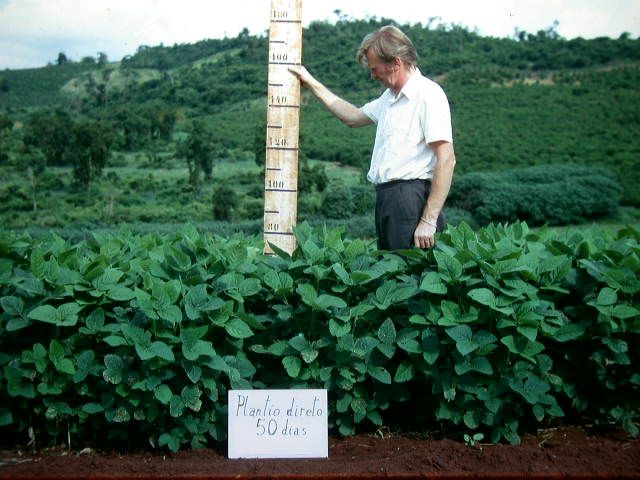

Born in Chile as the son of German emigrants, Rolf Derpsch would pave the way for no-till farming. On behalf of the German Agency for Technical Cooperation (GTZ), Derpsch came to Brazil in 1968 to set up trial stations at five locations, in the Southern state of Paraná.

„The soils were considered poor. Our job was to make them productive for agriculture.“ These were the early days of the Green Revolution and one of its basic ingredients – artificial fertilizer – was available by the bagful. All Derpsch had to do was determine the correct dosage.

Today, Paraná is considered Brazil's breadbasket, where export goods such as maize, soy, cotton and wheat are grown on a large scale. At the end of the 1960s, however, Derpsch found nothing but scarred earth.

Under Brazil's military dictatorship, deforestation exploded to make room for the expanding agricultural industry. The cleared areas were plowed intensively – with devastating consequences.

When the long dry season was followed by torrential rain, the dried-out soils could not absorb the water. „Those weren't erosion gullies but canyons,“ Derpsch recalls.

Entire fields slid off the hills during the rainy season. „All the topsoil was gone, just bare rock left.“ Derpsch made calculations: „For every ton of grain harvested, up to ten tons of soil were lost.“

This experiment conducted by researchers at the University of Reading shows very clearly what happened in Brazil: in lush, overgrown soil, water seeps away within a few seconds. The less vegetation, and the more bare and dried out the soil – the more impermeable the surface becomes. Dried-out soils turn hydrophobic, they become literally water-repellent.

As a result, the water does not infiltrate the soil, instead it runs off the surface. The larger the water masses, the steeper the slope, the more soil is washed away.

„Erosion is not an unavoidable natural phenomenon. Soil loss is nothing more than a symptom of the fact that an unsuitable cultivation system has been used on that field,“ Rolf Derpsch says. „It is not nature, but humankind that is responsible for erosion and all its negative consequences.“twortlich.”

During his time at German agricultural faculties in the mid-1960s, Derpsch had come across studies on no-till farming in the US. There, the horrors of the Dust Bowl years had shown that the plough – which until then had been regarded universally as an achievement of civilization – caused serious problems.

When Rolf Derpsch was gathering the equipment he wanted to bring with him to Brazil in 1967, he found what he was looking for at a small company in Hesse. So five seed drilling machines made in Germany laid the foundation for no-till in Latin America.

For the GTZ project called „Combating erosion in Paraná“, a Brazilian agricultural research institute provided the land on which Derpsch carried out his first trials with no-till farming in 1971. The effect was obvious: not using the plow stopped erosion. More and more farmers from the surrounding area adopted the new method. As previously in the US, no-till farming in Brazil in its early days was a movement led by farmers who wanted to free themselves from hardship.

From the mid-1970s, Derpsch continued his work in Paraguay, where he worked closely with the government. He organized seminars to train tens of thousands of smallholder families throughout the country in the use of no-till farming.

Derpsch vividly remembers when Norman Borlaug, the father of the Green Revolution, came to Brazil and Paraguay in 1995. He was impressed by the new form of agriculture he saw there. Derpsch quotes Borlaug with the following praise: "No-till farming is probably the most important revolution in agriculture at the end of this millennium."

„The introduction of glyphosate has made no-till farming affordable in the first place.“

Today, Rolf Derpsch is 86 years old. Looking back, he says: „To put it modestly, we created the conditions for the soy boom.“ More decisive than the artificial fertilizers, however, were the total herbicides, especially glyphosate, which came on the market in 1974: „RoundUp was sprayed directly onto the prairie and so the next field was ready.“

Since then, no-till farming has been on the rise worldwide, especially in arid regions where farming is otherwise becoming increasingly impossible. Today, 220 million hectares of land, around 15 percent of the world's arable land, is cultivated without plowing. China proclaims "no-till" as an integral part of its state-imposed agricultural policy since 2009. In countries such as the US, Brazil, Argentina and Australia, more than half of all land is under a no-till regime.

The glyphosate-soaked soy monocultures of the Midwest or the deforested Amazon as a model for sustainable agriculture? It's more complicated than that. The fact that less and less land is plowed is also a success story of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), for which the ban of tillage is the foundation of a farming philosophy dubbed "conservation agriculture". However, the FAO stresses that it is not enough to simply replace tillage with herbicides. The FAO has defined three principles that make "conservation agriculture" a sustainable cultivation system: Zero tillage, permanently covered soils and diverse crop rotations.

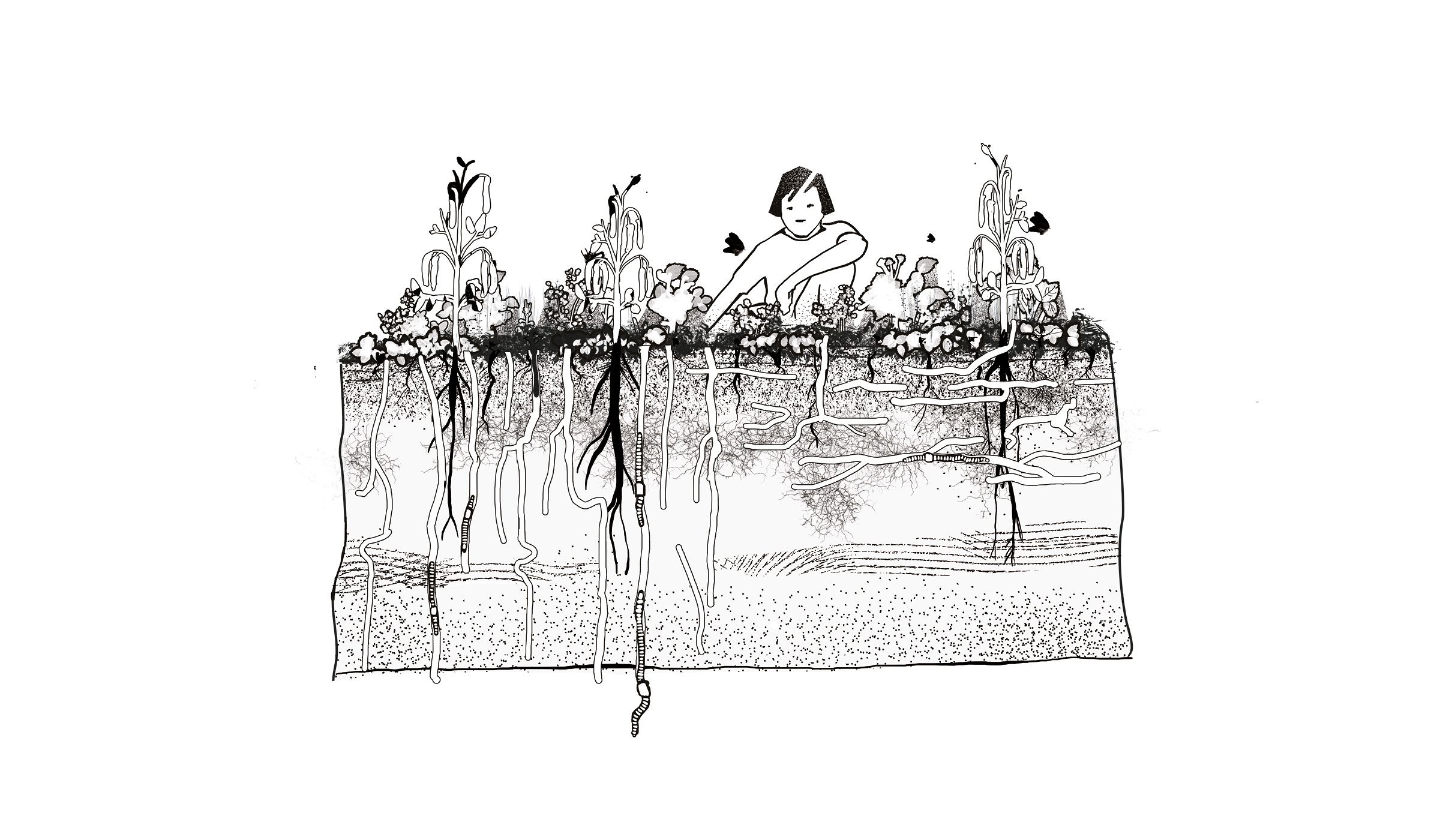

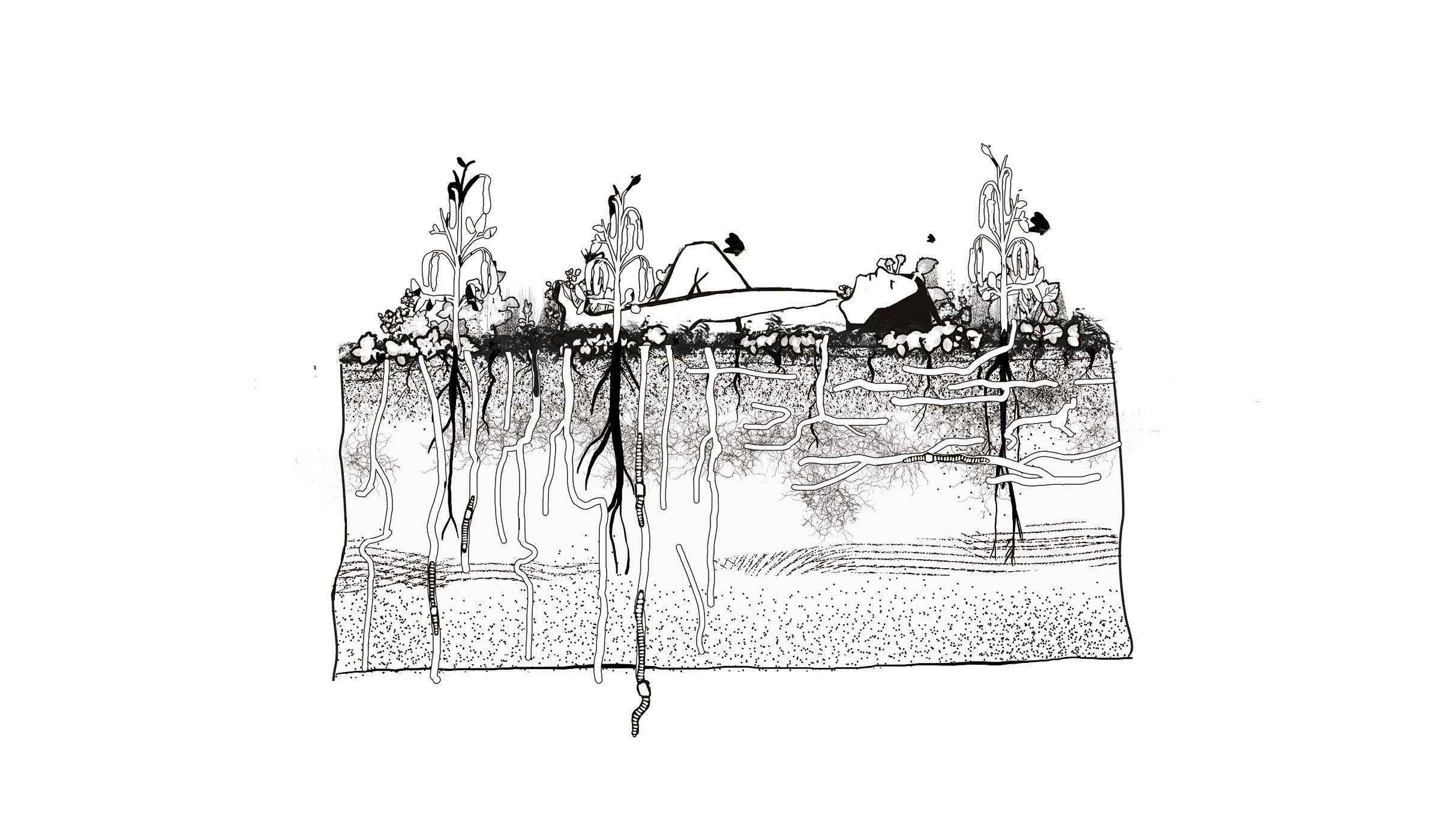

The soil needs protection.

Plants provide shade and cool the soil. When the plants die, they form a layer of mulch that protects the soil from wind and rain, frost and heat.

Roots loosen the soil and aerate it. Some plants root deeply, others shallowly. A fungal network runs through the soil and supplies the roots with nutrients.

As earthworms constantly dig through the soil, they distribute nutrients and create pores through which water can infiltrate the soil.

The more we leave the soil alone, the better the soil life can fulfill all its tasks.

„The plow is a weapon of mass destruction.“

Theodor friedrich, former FAO ambassador for sustainable food systems

Theodor Friedrich is convinced that we can still save the Earth's soils. „Conservation agriculture is not a theory, it is practiced globally in all climate zones.“ He knows because he was among a group of experts at the FAO who coined the term „conservation agriculture“ in the mid-90s. He has since worked to promote this way of farming. Until he retired in 2022, Friedrich served as an FAO ambassador for sustainable food systems in 75 countries – from Nicaragua to Burkina Faso to Kazakhstan and North Korea. In countries of the Global South, he says, small farmers in particular benefit from conservation agriculture. They don't even need machines, no-till can also be done with simple hand tools. However, Friedrich says that the rich industrial nations, as part of their „foreign aid“, prefer to keep on delivering tractors and plows to the Global South and thus continue to export their destructive version of agriculture.

While the plow causes erosion on the surface of the soil, the ever larger and heavier machines do their damage all the way down. Friedrich assumes that „our arable land is extensively compacted meters deep.“ A modern beet harvester, for example, weighs over fifty tons when fully loaded. Vehicles with such an enormous weight are no longer allowed on the road because they would cause too much damage to the asphalt. In their fields, however, farmers can roll such heavy equipment all over the unprotected soil, encouraged by martial names like Tiger S6, a beet harvester that can harvest 12 rows, or Warrior, a tractor in limited camouflage painting. These over-sized agricultural machines are the prestige objects of a global billion-dollar industry, which, according to Friedrich, is digging the grave for agriculture as such.

Friedrich, who first worked for the FAO's Plant Production and Protection Division, says that even people within the FAO defamed him as a lobbyist of the agrochem industry. He categorically dismisses this accusation, arguing that the use of pesticides decreases as soon as tillage is eliminated. “With good implementation – diverse crop rotations, lots of cover crops – farmers who practice conservation agriculture hardly spray any pesticides after a short period of time. Not because they aren’t allowed to – but because they don't have to.”

A plowed, bare field looks much very much like a desert. „Precisely this kind of desert is what you see, of all places, in organic farming, year after year“, with a large majority of organic farmers still relying almost obsessively on the plow, as Friedrich puts it. So do we ultimately have to make a trade-off: less erosion thanks to no-till agriculture – and, in return, accept the use of herbicides?

Herbicides have become an „indispensable part of conventional agriculture“, Friedrich says – „whether with or without a plow.“ In conservation agriculture, which does not require any soil cultivation, the use of weed killers can be greatly reduced, he argues. First of all, weed seeds would not be constantly brought to the surface and stimulated to germinate if farmers stopped moving the soil. „Secondly, weed pressure is reduced by a permanent, dense mulch cover, cover crops and diverse crop rotations.“ Finally, there is the possibility of killing weeds that emerge mechanically – with devices that do not harm the soil.

The agrochemical industry, however, has little interest in such a cultivation system, which requires less and less of the inputs it sells. „Companies like Bayer – and the forerunner in this question, Monsanto – initially had high hopes for no-till.“ Friedrich says, the companies „had hoped that glyphosate would be the only solution to salvation, particularly in combination with herbicide-resistant crops, which led to a real boom in sales of glyphosate and contributed to the current problems with the product.“

In fact, no-till farming received a huge boost in the mid-1990s when Monsanto entered the market with genetically modified seeds that were resistant to the company's herbicides. Soon, the cultivation of corn and soy in the US and Latin America became unbeatably efficient with this new package of herbicides and resistant varieties. Unwanted vegetation could now be killed while the genetically modified crops continued to grow undamaged.

Monsanto used the idea of „conservation agriculture“, which Theodor Friedrich promoted as a sustainable farming philosophy on behalf of the FAO, for its own purposes. From the mid-1990s, Monsanto partly financed and participated in dozens of projects in the Global South where governmental foreign aid organizations and private foundations spread the new package of no-till and herbicide-resistant varieties. In Ghana alone, Monsanto taught around 100,000 small farmers the basics of no-till farming around the turn of the millennium. At that time, researchers interviewed local dealers who sold the necessary inputs to the new no-till farmers. Two-thirds of retailers reported that their herbicide sales had doubled or even tripled within a very short period of time.

Such projects had nothing to do with conservation agriculture, as defined by the FAO, Friedrich criticizes, as there was hardly any mention of crop rotation or soil cover. Monsanto certainly did advance no-till agriculture, Friedrich says, „but only in combination with glyphosate and resistant plant varieties. That's the old paradigm of the Green Revolution.“

Green Revolution 2.0

Genetically modified soil microbes, the „intelligent field“ and dubious CO2 certificates: the agricultural industry has discovered soil as a product. Meanwhile scientists unearth the true scale of contamination in our soils.

Contents

Chapter I

Losing Ground

Preserving soils is not only key in the fight against hunger. Healthy soils also help us to brace the climate crisis, droughts and floodings as well as the mass extinction of species.

Chapter II

Worn out

The plough and artificial fertilizers drastically increased yields, but they have long devastated the Earth. In the age of the soil crisis, we need to rethink agriculture from the ground up.

Chapter III

Green Revolution 2.0

Genetically modified soil microbes, the „intelligent field“ and dubious CO2 certificates: the agricultural industry has discovered soil as a product. Meanwhile scientists unearth the true scale of contamination in our soils.

Chapter IV

Regenerated

The agrochemical industry is eager to avoid restrictions to its farming model, politics are postponing soil protection. Against all odds, the soil-building agriculture of the future already takes shape on more and more fields.

by Marius Münstermann

videos & photos Christian Werner

illustrations Erik Tuckow

editor Wolfgang Hassenstein

Recommended books, podcasts, films & organizations

Jared Diamond - Collapse. How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed

European Alliance for Regenerative Agriculture (EARA)

European Land and Soil Alliance (ELSA)

Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) - Status of the World's Soil Resources (2015)

Life in the Soil - Podcast produced by the FU Berlin's Institute for Biology

David R. Montgomery - Dirt. The Erosion of Civilisations

No-Till Growers - YouTube channel about regenerative farming

Pesticide Atlas - Facts and figures about toxic chemicals in agriculture

Joshua Tickell, Rebecca Harrell - Kiss the Ground (documnetary)

Music used under Creative Commons licences

Betelgeuse - Kunal Shingade

Golden Hour - Lakey Inspired

Filaments - Scott Buckley

Dub Trippin - MK2

Reloaded - Savfk

The Dreamer - Lakey Inspired

The Uprising - Arthur Vyncke

Uncertainty - Arthur Vyncke

Ethereal - Punch Deck

Supported by a fellowship of the

Additional footage has been provided by

BASF - BASF Archive

Bayer CropScience

Julian Chollet, Gesellschaft für mikroBIOMIK e.V.

Deutsches Zentrum für integrative Biodiversitätsforschung / TRICKLABOR

Rolf Derpsch

depositphotos.com

Mark Dümichen, "Wir mögen es grün"

EU Soil Observatory

fortepan.hu / Veszprém Megyei Levéltár/Klauszer

Maria Giménez, Wilmas Gärten

Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung

International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT)

André Künzelmann/Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung UFZ

Dorothea Lange / Library of Congress

Ellen Larsson, R. Henrik Nilsson, Erik Kristiansson, Martin Ryberg, Karl-Henrik Larsson: Approaching the taxonomic affiliation of unidentified sequences in public databases – an example from the mycorrhizal fungi". BMC Bioinformatics

Martin Leick

Ignacio Romero Lozano, Forschungsinstitut für biologischen Landbau (FiBL)

Kevin McElvaney

Miguel Á. Padriñán

Pestizid-Atlas 2022 / Umweltinstitut München e.V.

pexels.com

picture alliance / ASSOCIATED PRESS (portrait photo of Norman Borlaug)

pixabay.com

Photograph from 1892 of a pile of American bison skulls

Robert Thompson, University of Reading

Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision